My PhD research

So what does

I'm interested in what happens when students in higher education work collaboratively in a maths learning support setting

mean?

THE SPECTRE OF MATHEMATICS

Suppose you're a student just starting your first year of university in, say, a nursing degree. You're excited to start your classes. To meet your classmates. To learn new ideas and new skills! And so on. Then, all of a sudden, one of your lecturers starts talking about "drug calculations", and division, and ratios, and units...

Suddenly, you're thrust into a tangle of maths problems. What do you do? You were under the impression that once your secondary school days were finished, you would never have to do a maths problem again in your life. You thought you were free of it! And now the ghastly spectre of mathematics has come back to haunt you.

Okay, stop supposing and be yourself again. You might find it odd that someone could have such a strong a reaction to maths returning into their life. On the other hand, you might not. A lot of folk have a pretty strong negative reaction to maths, sometimes called 'maths anxiety'. In some cases, this maths anxiety is so overpowering that it can lead to a panic response.

Heartrates rise, breathing is difficult and palms sweat... [it leads to] the release of brain chemicals associated with fear (1, p.77)

What's going on here? How does this happen? And what can we do to help this student?

AN UNWITTING FORM OF COGNITIVE ABUSE

Maths anxiety has no single definitive cause. Some of it comes from experiences of shame or embarrassment.

One student, when it was realised they were not paying attention, was asked to solve a mathematics question on the whiteboard in front of their class, and they did not know the answer. They became known as the 'stupid' student. Similar stories were shared by many of the participants (2, p.182)

Some of it comes as an effect of rote learning maths. When maths is taught by rote, and not for understanding, it becomes "an unwitting form of cognitive abuse" (3, p.4). This cognitive abuse has consequences.

Abuse results in damage; cognitive abuse or neglect results in damage to the way that pupils think about mathematics (4, p.56)

And some of it comes from teachers and parental figures who themselves have maths anxiety. Female students are more likely to develop maths anxiety if they had a female maths teacher with maths anxiety (5). Teachers and parents can pass down internalised negative beliefs about maths, reinforcing stereotypes about mathematicians. Who would want to invest in learning maths, if mathematicians are all:

Boring, obsessed with the irrelevant, socially incompetent, male and unsuccessfully heterosexual¹ (6, p.214)

Suffice it to say that there are many very understandable reasons why someone might develop an aversion to maths.

Alright, so that's where maths anxiety comes from. Now, how do we help that nursing student?

MATHS SUPPORT

One very practical way to help a student in this kind of situation is to sit down with them, help them relax, and walk through their maths problems with them in a non-judgemental, compassionate way. This solution is the one offered by maths support centres. Mathematics Learning Support (MLS from here on out) is

A facility offered to students (not necessarily of mathematics) which is in addition to their regular programme of teaching through election, tutorials, seminars, problems classes, personal tutorials, etc. (7, p.9)

Most² institutions in Ireland and the UK that provide MLS do so in the form of a room where students can go to get help with their maths problems, known variously as a 'maths drop-in', 'maths learning centre', etc. I'll refer to it here as a 'MLS centre'.

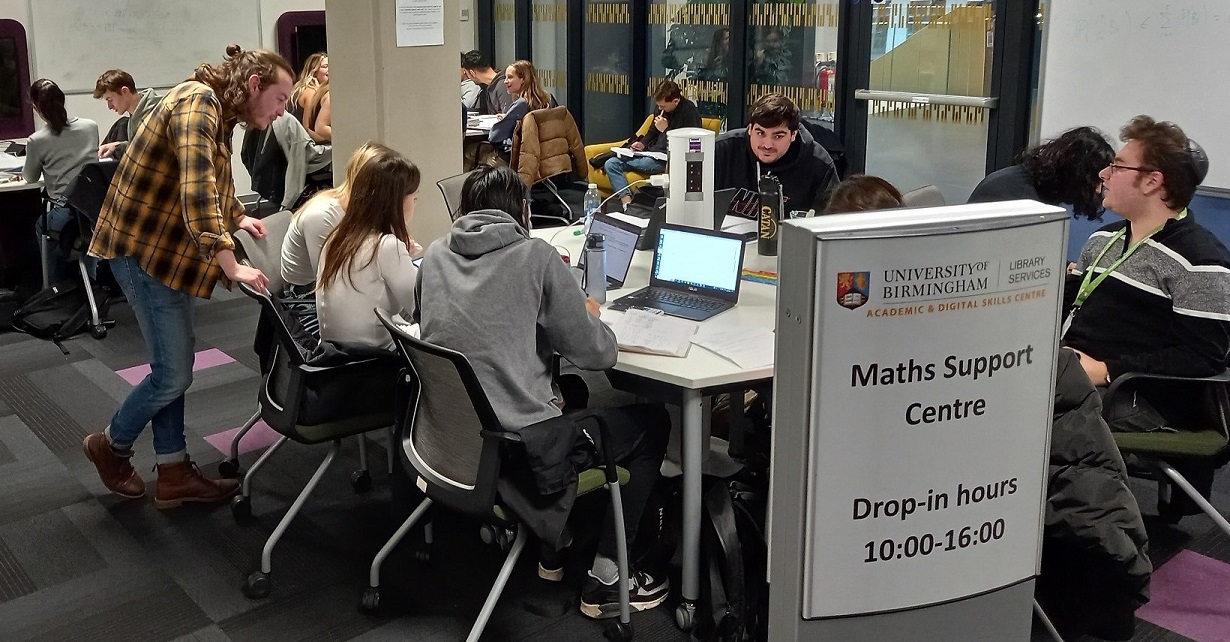

A typical scene in a maths support centre. Students can be seen sitting around a large table together and discussing their assignments. Source: University of Birmingham.

In MLS centres, students can come to chat with a maths tutor, work on their maths assignments, access resources (such as worksheets and textbooks), and so on. It's a friendly space to do maths.

MLS centres have multifaceted impacts on the students who attend beyond simply helping them with assignments and exams. It helps students build confidence when approaching maths problems (8) and have more confidence generally in their mathematical abilities (9). It's an important factor in helping many students not drop out of their degree (10,11)³.

Now, usually students come to an MLS centre to chat to a tutor one-on-one. However, sometimes a cohort of students will get into the habit of coming to a MLS centre as a group, engaging with the tutors as a group, and generally working collaboratively on their maths problems. This kind of engagement has seen much less study, but can have a profound impact on students.

COLLABORATION IN MATHS

Now this is what I'm really interested in and excited about. See, maths in school and maths in pop culture lead people to view maths as an isolated pursuit (see above quote). You do your own individual work to find your own individual answer to get a higher score than the other students. Working mathematicians, on the other hand, know that maths is a necessarily joint endeavour. Browse through arXiv's most recent maths submissions and you will find most written by a team, often of four of five different people.

Famous mathematicians and physicists known for singular intellects were usually not so singular. To decode the Enigma machine during WWII, Alan Turing worked in collaboration with Gordon Welchman to improve the Polish Bomba, which was in turn design by Marian Rejewski, a Polish cryptologist⁴.

Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity would not have been possible without the help of his friend and collaborator Marcel Grossmann. The first iteration of the theory, published in 1913, was a collaboration between the two.

Grossman and Einstein during their college days together. Source: The American Institute of Physics.

The most quintessential example of a maths hermit I can think of, Andrew Wiles, could not have completed his 7-year struggle to prove Fermat's last theorem without the help of his former student, Richard Taylor. The final proof of the theorem was published in 1995 across two papers, the second of which was authored by both Taylor and Wiles.

Some mathematicians are famous for exactly the opposite reason. Hardy and Littlewood's lifelong collaboration was so successful that Danish mathematician Harald Bohr once wrote:

I may report what an excellent colleague once jokingly said: 'Nowadays, there are only three really great English mathematicians: Hardy, Littlewood, and Hardy-Littlewood.' (12, p.xxvii)

Through his mathematical career, Paul Erdős published with over 500 collaborators, leading to the coining of the Erdős number, a measure of degrees of separation from Erdős via authorship on published papers.

COLLABORATION IN MLS

So I think it really stands to reason to that students might get something out of mathematical collaboration themselves. Now, there's a 2010 paper called Safety in numbers: mathematics support centres and their derivatives as social learning spaces, detailing a study carried out by Solomon et al. (13) about the experiences of students working collaboratively in two MLS centre in the UK. The paper discusses the profound effect this collaboration has on the students.

[There is a] collective refiguring by the Farnden and Middleton students which counters the dominant view that mathematics is an isolated pursuit. ... The Middleton and Farnden students appear to collaborate across 'abilities', and their ethos in practice tends towards a recognition that everyone has different perspectives and understandings. (13, p.429)

The students in this study dispelled many of the usual stereotypes and stigma about maths. They worked together to understand lecture notes and coursework. It gave students a kind of safety net. In an interview, one student put it:

Because we've worked so well together beforehand I know that if I get stuck I can ask them, and if they get stuck they can ask me (13, p.428)

Working together became a central part of how they learned. As another student put it:

I think most of the learning is done through helping each other, everyone's got their strength and weakness... (13, p.430)

This paper really resonates with my own experiences. When I was working in the support centre in DCU, I saw this kind of collaborative engagement all the time. A large portion of the first- and second-year maths students would regularly attend the support centre, working in groups to figure out their assignments and lecture notes.

Interacting with those students felt less like the usual interactions typical of students and tutors in a support centre, and more like the experiences I had helping my friends during my undergrad. While it was still a tutor-student dynamic, it was much more casual. It felt like the students were more open about what they were struggling with.

A STUDY OF COLLABORATIVE LEARNING

These very interesting points are just the results of one study from 14 years ago concerning two support centres, and my own anecdotal experiences of one support centre. Three data points does not convincing evidence make!

I think that this kind of collaborative learning, like I experienced in DCU and like Solomon et al. described in their study, could have a huge impact on other students in other universities. It could also have a big impact on students who have maths anxiety. Right now, we don't know the details. That's what I want to find out.

Exactly what impact does collaborative learning in MLS centres have on students? Does it help students with maths anxiety? Can you gear a MLS centre towards collaborative learning? How?

Answers to these questions may help MLS practitioners provide better support for more students. We'll see how the data collection goes, anyway. :)

FOOTNOTES

¹ This last part might be less relevant if you're a friend of Dorothy, but the other stuff still stands.

² 64% in Ireland as of 2016 (14), 82% in the UK as of 2018 (15). My guess is that these numbers have gone up since then, but I don't have any more recent references for you.

³ There's a laundry list of studies showing the impacts of MLS on students. Some major studies to look at are the 2014 IMLSN report (10), and the reviews of MLS literature by Matthews et al. (16) and Lawson et al. (17), which both reference many previous studies.

⁴ In fact, the Poles had been breaking Enigma messages for over six years with the Bomba before sharing the technology in 1939.

REFERENCES

(1) Watson, A. (2021). Care in Mathematics Education: Alternative Educational Spaces and Practices. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64114-6

(2) Gokhool, F. (2023). An Investigation of Student Engagement and Non-engagement with Mathematics and Statistics Support Services [Doctoral dissertation, Coventry University]. https://pureportal.coventry.ac.uk/en/studentTheses/an-investigation-of-student-engagement-and-non-engagement-with-ma

(3) Johnston-Wilder, S., & Lee, C. (2010). Developing mathematical resilience. https://oro.open.ac.uk/24261/2/3C23606C.pdf

(4) Johnston-Wilder, S., & Lee, C. (2008). Does Articulation Matter when Learning Mathematics? Proceedings of the British Society for Research into Learning Mathematics, 28, 54–59. http://www.bsrlm.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/BSRLM-IP-28-3-10.pdf

(5) Carey, E., Devine, A., Hill, F., Dowker, A., McLellan, R., & Szucs, D. (2019). Understanding Mathematics Anxiety: Investigating the experiences of UK primary and secondary school students. https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/handle/1810/290514

(6) Mendick, H. (2005). A beautiful myth? The gendering of being/doing ‘good at maths’. Gender and Education, 17(2), 203–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/0954025042000301465

(7) Lawson, D., Croft, T., & Halpin, M. (2003). Good Practice in the Provision of Mathematics Support Centres (2nd ed.). https://www.mathcentre.ac.uk/resources/guides/goodpractice2E.pdf

(8) Gillard, J., Robathan, K., & Wilson, R. (2012). Student perception of the effectiveness of mathematics support at Cardiff University. Teaching Mathematics and Its Applications: International Journal of the IMA, 31(2), 84–94. https://doi.org/10.1093/teamat/hrs006

(9) Carroll, C. (2011). Evaluation of the University of Limerick mathematics learning centre [BSc Dissertation, University of Limerick]. http://www.mathcentre.ac.uk/resources/uploaded/evalmaths-l-centrelimerickcarrollgillpdf.pdf

(10) O’Sullivan, C., Mac an Bhaird, C., Fitzmaurice, O., & Ní Fhloinn, E. (2014). An Irish mathematics learning support network (IMLSN) report on student evaluation of mathematics learning support: Insights from a large scale multi-institutional survey [Monograph]. National Centre for Excellence in Mathematics and Science Teaching and Learning (NCE-MSTL). https://doras.dcu.ie/22489/

(11) Ní Fhloinn, E., & Deacon, L. (2023). The Impact of Mathematics Support upon Student Retention: The Student Voice. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.10037373

(12) Bohr, Harald (1952). "Looking Backward". Collected Mathematical Works. Vol. 1. Copenhagen: Dansk Matematisk Forening. xiii–xxxiv. OCLC 3172542.

(13) Solomon, Y., Croft, T., & Lawson, D. (2010). Safety in numbers: Mathematics support centres and their derivatives as social learning spaces. Studies in Higher Education, 35(4), 421–431. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070903078712

(14) Cronin, A., Cole, J., Clancy, M., Breen, C., & O'Sé, D. (2016). An audit of Mathematics Learning Support provision on the island of Ireland in 2015. National Forum for the Enhancement of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education. https://pureadmin.qub.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/135272903/MLS_Ireland_survey_2015.pdf

(15) Grove, M., Croft, T., & Lawson, D. (2020). The extent and uptake of mathematics support in higher education: Results from the 2018 survey. Teaching Mathematics and Its Applications: An International Journal of the IMA, 39(2), 86–104. https://doi.org/10.1093/teamat/hrz009

(16) Matthews, J., Croft, T., Lawson, D., & Waller, D. (2013). Evaluation of mathematics support centres: A literature review. Teaching Mathematics and Its Applications, 32, 173–190. https://doi.org/10.1093/teamat/hrt013

(17) Lawson, D., Grove, M., & Croft, T. (2020). The evolution of mathematics support: A literature review. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 51(8), 1224–1254. https://doi.org/10.1080/0020739X.2019.1662120